The Fascist conception of the State is all-embracing; outside of it no human or spiritual values can exist, much less have value. Thus understood, Fascism is totalitarian, and the Fascist State—a synthesis and a unit inclusive of all values—interprets, develops, and potentiates the whole life of a people.

— Giovanni Gentile

In the series of my articles on FA Hayek, I have addressed several labels that are often tossed about the political and cultural landscape. People are often accused of being Nazis, Communists and Socialists. So I am asking my readers to consider whether they understand what these labels mean. I now address the label of “Fascist.” Note, it is with a capital “F”. It is interesting that of all the labels, Fascist is the only one that seems to have morphed into its own adjective. So if someone accuses me of being fascist, I have to ask whether they mean the small-case “f” or the capital letter.

A Word Without Meaning

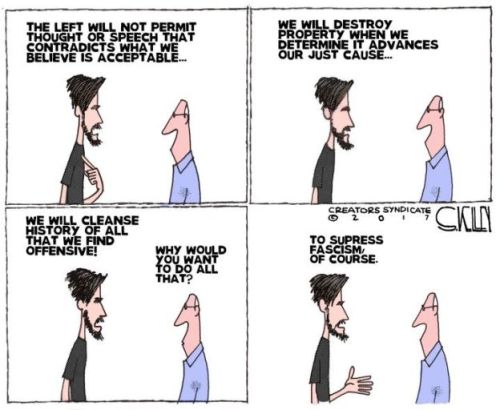

The point of this article is to discuss Fascism. But before doing so, an explanation is needed as to why the word “fascist’ is meaningless. When a word comes to denote everything, it is reduced to meaning nothing. The word “fascist” has no etymological footing. While in the 1920’s and 1930’s being “fascist” was clearly applying Fascism, the use of the word in the US today is anything from wearing a brown shirt, owning a gun, or voting for Trump. In essence, the word “fascist” is a general description for a person you do not like. By generalizing the term to apply to people you dislike, you rob yourself and the people around you the truth about Fascism. The irony is that the very people who accuse people of being fascist are actually Fascists, not because they wear brown or black shirts, but because of their ideology based on collectivism, and their enthusiasm for using the State to enforce their social agenda on others.

Even back in the 30’s Hayek would observe how the British would be confused over the term “fascist.” For them, and to many of us today, Nazis were Fascists. But Germans were no more Fascists than they were Italians. Observers were surprised that the influx of German socialists who immigrated to Britain during the 1930’s held what many would consider “fascist” views.1 It would be Hayek’s assertion that this was a classic Western blunder, labeling Fascism as a far-right ideology and that the divide between the Nazi’s and the Socialists/Communists of Germany was that of the Left against the Right. When they discovered their newly arrived immigrants, many of whom were either socialists or communists, held “fascist” views on how to deal with society’s problems, they were confused, failing to understand that this was a fight amongst socialists.2

Rooted in Collectivism

For clarification, let’s begin with the roots of Fascism. Fascism was a movement that seized control of the government of Italy in 1922. It was led by Benito Mussolini, who began his political career as a socialist. He relied heavily on the writings of Giovanni Gentile, who championed a collectivist state. The word is derived from the Latin “fasces” which describes a bundle of wheat. In essence, strength in unity. In Gentile’s words,

The Fascist conception of the State is all-embracing; outside of it no human or spiritual values can exist, much less have value. Thus understood, Fascism is totalitarian, and the Fascist State—a synthesis and a unit inclusive of all values—interprets, develops, and potentiates the whole life of a people.

It could be argued that Gentile was a classical socialist, and not a Marxist. But both philosophies rely on an elite that determines what is best for society. Hayek would quote British journalist FA Voigt. “Marxism has led to Fascism and National Socialism, because, in all essentials, it is Fascism and National Socialism.”3

If you are not a collectivist, you are not a Fascist. And note once again, how Voigt distinguished the two movements.

Hayek and Fascism

Since this is part of a series on The Road to Serfdom, we need to explore how Hayek treated the subject. The book is a critique on socialism and he goes to great length to explain how Nazism and Fascism are part of the same ideological tree as socialism. Yet we need to remember that when he first wrote The Road to Serfdom, elements of the book first emerged in 1933 and his perspective matured throughout the 30’s when the book was first released in 1938. His use of the term “Fascist” needs context. When reviewing the subject, I made the following observations:

- Space in the Index – What struck me at the outset was how the Index only had a small section devoted to Fascism. The book is richly indexed, so in comparing with other subjects such as “socialism” or “Nazism” the subject of Fascism is given short thrift.

- Reviewing the references in the index and a few locations that were not indexed, it is evident that Hayek treated Fascism realistically, as a derivative movement born from the foundation of socialism that was uniquely applied to the politics of Italy.

- Fascism and Nazism are treated separately. Hayek’s treatment of Fascism reflects, in some part, to his being a German. His experience was with German politics and economics and it is natural that his material reflects that experience. His concern regarding the totalitarian tendencies of socialism was proven by what he observed amongst the Nazi’s. He distinguished Nazi ideology from Mussolini’s Fascism and he recognized that what led each to power was a unique path.

It is also important to note another author who strangely dismissed the term Fascism. No book is probably as revered on the history of Nazi Germany than William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.4 Of the 1143 pages in the book, not one listing in the Index has a reference to Fascism. As with Hayek, Shirer was describing a German experience, and Fascism was viewed by him as an Italian experience.

Throughout Hayek’s book he builds a case that both National Socialism and Fascism were attempts to resolve severe economic and social disturbances. Italy was only formed as a nation in 1861 and had been devastated economically and socially by World War I. Germany, of course, suffered the humiliation of the Versailles Treaty, followed by the hyper-inflation of the Weimar Republic and the effects of the Great Depression. Both movements were unique attempts to build on socialist ideology a layer of pragmatism that discarded the Utopian aspect of Marxism, advancing techniques that would achieve the objectives of the State and bring prosperity, pride and order to society. It is interesting how Hayek included Peter Drucker’s perspective, that “Fascism is the stage reached after communism has proved an illusion, and it has proved as much an illusion to Stalinist Russia as in pre-Hitler Germany.”5

Hayek also had the opinion that the rise of Fascism and Nazism had their roots in what appears to be a “middle class” movement, rather than the typically held view of being a working-class movement. In both Germany and Italy, a politics of envy emerged fueled by the unemployed university-trained workers, a so-called “white collared proletariat.” They were displeased with the lock socialists had on the labor unions (or vice versa), advancing policies of which they never benefited. In other words, labor unions were part of the problem. And their control of established socialist parties was a problem that could only be solved by creating a different party.6

In essence, all factions had the same ideology regarding state control of the economy and of society. The question was who would control whom. Who should gain, and who should lose? As history would bear out, the labor unions and the established socialist parties were the big losers. Labor was to submit not to the interest of the owners of the means of the production (the capitalists), but to the State.7

In his chapter “The ‘Inevitability’ of Planning,” Hayek commences with a quote from Mussolini.

We were the first to assert that the more complicated the forms assumed by civilization, the more restricted the freedom of the individual must become.8

In essence, individualism is old fashion. What Mussolini stated would be repeated in Germany, the Soviet Union, China and North Korea.

In Conclusion

So the question of whether you are a Fascist is embarrassingly easy to answer. Fascism emerged from collectivism which justifies the use of the State to enforce conformity of the individual. I think that this should cause all to pause and reflect.

Fascism provided a model that the National Socialists in Germany utilized as they saw fit. Marxism, Communism and Socialism in most cases advanced the notion that the State must control the entire economy. Fascism broke away from that aspect of Marxism, enabling the economy to be entrepreneurial, but in conformity to the interests of the State. Both Italy and Germany would see phenomenal rates of economic growth prior to World War II.

Is there an example of a Fascist state today? The Peoples Republic of China (mainland China) is about as close to the Fascist model as anyone these days. The results have been breathtaking as China has emerged from an agricultural, impoverished society, to the second largest economy in the world today. They did so by discarding the Marxist tenet that the State must control the entire economy. They recognized that independently owned companies could best deliver a higher living standard to its people. Yet entrepreneurial energy, innovation, growth and prosperity are merely granted to anyone who can succeed. The State has the authority to take it all away and the State has the power to access customer data, seat members of the party on boards, and abscond profits.. It is interesting to observe that China is also following the same pattern of evolution as Italy and Germany. At some point, all that economic power needs to be directed outward. China has routinely laid claim to large sections of the South China Sea and the Pacific, while threatening Taiwan. And, sadly, China has also advanced a social model that has persecuted Muslims and Christians, and targeted ethnic groups. And as Mengele experimented on prisoners, so China has conducted organ harvesting on prisoners.

Footnotes

1 We need to note that the British were concerned that Nazi infiltrators could be mixed into the immigrant population.

2 The Road to Serfdom, FA Hayek, University of Chicago Press, 2007, p.62

3Hayek, p. 79

4The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, by William L. Shirer, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1960.

5Hayek, p. 80

6Hayek, p.144

7Hayek, pp. 144, 145

8Hayek, p. 91

© Copyright 2023 to Eric Niewoehner